The Plymouths - a band dynamic foreshadowing Beulah, leaving Wisconsin for sunny California, where it rained for two weeks straight upon arrival to SF

Go South and Take a Right

One rainy afternoon in March of ’92, I got a random knock on the door. It was John Dannenbrink, and he was carrying a guitar. Greg Norman and I had met John at an open mic at the Memorial Union about a year before. We got to talking and tried him out to play lead for Strange Bedfellows, but it didn’t work out. We hung out a couple of times after that, goofing off on guitars, writing joke songs on the fly, pieces of covers we knew, mashing up songs like “Summer Breeze” into “Helter Skelter” (“Blowin’ through the Jasmine of my miiiiind, yeah yeah yeah!”).

When he graduated from UW in ’91, I figured I’d never see him again. But John was a man of mystery. I started getting these weird post cards from random faraway places like Ely, Nevada signed “Gary Davis” with no commentary. This was a nickname John had given himself before he left, and I had no idea why. I knew nothing about the old bluesman, Reverend Gary Davis, in those days.

When John came back, he had songs of his own that he wanted to play. He started singing and my jaw dropped. What a voice! I can’t believe I hadn’t heard him sing before. Great songs, too. Pretty soon we were playing in the round, adding our own instrumentation to each other’s tunes, and by the time summer approached, we had an album’s worth of material.

This is the first time I found myself in a support role for someone I considered a stronger songwriter. One of my favorite songs of his is called “Marilyn Monroe.” He has a dream where he meets Marilyn and at the end of the song she asks him for directions to get to Hollywood. He says:

She came to me in a dream, in a dream

Just a-lookin’ for Hollywood, Hollywood

She came to me in a dream in a dream in a dream

I said to myself she just wanted directions

And her slippery dress was magnetic

So before I went back to bed, I said “M’am…

Go south and take a right, look for lights when you hit the Coast”

John would later bonk himself on the head, pointing out a critical error in this verse by asking why he would be going back to bed when he was already asleep and in a dream. I wasn’t quick witted enough back then to ask “Who’s to say there wasn’t a dream within a dream?”

I asked Jeff Jagielo if John and I could go up to his studio to record some songs. Jeff did more than just record - he became a direct participant, playing electric guitar on most of the tracks and singing backup vocals with us. John came up with our name: les plymouths. He had an ‘84 Plymouth Turismo and I had a ’77 Plymouth Fury, and he thought it would be more interesting if we were “The Plymouths” in French.

L to R: les plymouths - 1977 Plymouth Fury, 1984 Plymouth Turismo - December, 1992

We recorded more of my songs than his, but that’s just because I had more. I felt then, and maintain now, that John’s songs were better. He had a little bit of country in him, like Hank Williams Sr. maybe.

In fact, it was John who broke down a barrier I had put up to country music while growing up. As a kid I associated it with the rednecks in town standing in a circle, stomping their boots way off the beat to “Bocephus” (Hank Williams Jr.) at the high school dance. But John introduced me to the elder Hank, among others, and that served as a reminder that a great song is a great song, no matter what the accent is.

Greg Norman joined us for one session with an upright bass he had “acquired” from his high school. He played most of his tracks on the fly, and usually nailed them in one take. If there were any mistakes, he was one of those players that could make it sound like he meant to do that by what he played next. This was the project that also taught me to let the songs breathe – to slow the fuck down.

John and I went up north to record a few more times that summer, adding things like lap steel, slide guitar, and Jeff would add a ton of electric guitar and other treatments in his own time.

John Dannenbrink, playing the bottle

The Plymouths was an important project because, without it, I don’t think I would have ever ended up being in Beulah. The seed was planted here. To this point I had only been in bands as a front person. I had vague ideas about wishing I could take a backseat in a band dynamic, but never seriously entertained joining one as a role player. I didn’t think I was good enough of a musician at any one instrument, certainly not lead guitar. And I didn’t think joining a horn section on trumpet was in the cards; my sight reading was terrible. I learned how to play drums by watching other people and then sneaking onto their drum sets later, but I never took drumming too seriously, though I was interested in getting better at it. I also hadn’t yet considered learning about recording in more depth. This project showed me that it was possible to lower my inhibitions about all that – and let go of my ego about having to be the lead singer with my own songs most of the time. Jeff Jagielo’s basement in Plover, Wisconsin was a safe space to try anything. I’d play a little of all of those instruments I mentioned for The Plymouths. But more importantly, I learned, little by little, more about recording by watching Jeff work.

Me, playing Jeff’s Paul Reed Smith, trying to look like I can shred or something…

Meanwhile, Strange Bedfellows had still been going but was winding down. In May, Todd had announced that he was going to move to South Carolina to get his graduate theater degree, so that meant Greg and I needed to find a new drummer. Todd asked me if I wanted to move with him to South Carolina, but I never considered it. I told him that I was “committed to Greg.”

Todd’s parting was not amicable. After a strange gig opening for Ivory Library at the Lake Monona Club, a jazz joint where we dressed up in shirts and ties and all played sitting down, Todd went heavy on the cocktails. Some people are happy drunks. Not Todd. He turned out to be a scary drunk, in fact. And Greg and I had just paid for the “Down, Down, Down” cassette pressing a while back, but Todd hadn’t paid for his share yet. And when I told Todd that Greg and I were going to take his cut of the gig to pay for the tapes and that he still owed us money after that, he flipped out. Then, stupidly, I added fuel to the fire when I told him that he should stop “talking out of his ass.” That didn’t go over well.

Next thing I knew he was outside smashing his floor tom in the middle of the street, and when a friend of Ivory Library’s drummer went out there to stop him, thinking it belonged to them, Todd turned and screamed at the guy to leave him alone or he would strangle him. I learned later that he moved up to Vermont with his girlfriend to pick blueberries. I wouldn’t hear from him again for a good long while. Todd was a great guy, just don’t add hard liquor.

Greg and I started looking for new drummers that summer, but by August we hadn’t gotten anywhere. Meanwhile, I was graduating from college and having second thoughts about what my next move was going to be. I hadn’t gotten an apartment yet and needed to move out of my current one by the 15th.

Jason Ries, one of my best friends from Berlin, went to Marquette University over in Milwaukee and had also just graduated. Jason was around for many key moments in my musical life. He sat next to me in the trumpet section in the junior high band and was one of the few smart people to laugh at my jokes. He’d been a straight “A” student, while I was always getting into trouble and goofing off. Even though we’d known each other since we were nine, we didn’t hang out outside of school functions until the summer before I moved to Chicago. He and I became close friends after that, and we kept in touch through college. He was there for a couple of Rapture/Absent Presence gigs, including a pilgrimage we took to Berlin in August of ’88 where we rented out the local Eagles’ hall. He would visit me in Madison often and was there at the party when Jim Dixon introduced me to Greg Norman.

After our graduation in the summer of ‘92, Jason was going to move to Madison with me to “slack” for a while and we began looking for apartments in August. On the 15th I had to move out of my apartment and took all of my stuff down to my parents’ house in Villa Park. I landed a job at the University Bookstore in Madison and was to start on September 1st. Jason and I planned to go to Madison on weekends and crash at Greg’s apartment while we looked for our own. The first night we were there, must have been August 20th, we decided to have a couple of beers at Amy’s Café, where a lot of the international students used to hang out. It had been a long, unsuccessful day of apartment hunting. I liked Amy’s because you could pretend you were living in Sao Paolo or Paris. There were people from all over the world having a coffee or a beer.

A couple of beers turned into a couple of pitchers and then Jason and I took stock of our situation. I said to him, half joking, “Maybe I don’t want to live in Madison anymore.” Jason said, “it’s funny you mention that, because I was going to ask you about moving to San Francisco.”

San Francisco? I knew he wanted to pursue a film career and wouldn’t have been surprised if he’d said LA (where I knew I wouldn’t want to live), but San FRANCISCO? I had never been to San Francisco. But there was someone I’d dated the previous summer who had moved there.

In the summer of ’91, my dating life was sporadic at best. I wasn’t really mature enough to have a steady girlfriend – things just didn’t work out for one reason or another. Up until I met my wife, Kiera, in 1996, I only had one other relationship that had lasted more than two months.

I remember it was July 4th, and this encounter would turn out to change the course of my life, though I had no way of knowing it at the time. I was up in Green Lake, a few miles from Berlin, having beers with Jason and a couple other buddies at a bar called the Goose Blind. Green Lake was kind of a tourist town, one of many places in Wisconsin where people from Chicago had long ago scooped up valuable lake front properties, and this bar was the watering hole of choice for people from all over. As someone who had lived in the Chicago area for three years by that time, it was a place I felt more comfortable. Wisconsin has no shortage of bars – its per-capita rate of bars per town block is the highest in the country. But most of ‘em were redneck bars, and I needed just a little more cultural diversity. This is another way of saying the women were better looking and more interesting at the Goose Blind.

To make a long story short, I met a woman named Kristin McCarthy at the jukebox that night and we dated for the rest of the summer. She and a couple of her friends worked at a resort called the Heidl House to save up money, as they were on their way to San Francisco from upstate New York, where they had just finished up at Wellesley College. Kristin and I kept writing letters to each other after they moved on to San Francisco, but I had also moved on by the summer of ’92, though I had entertained the possibility of going out there for a visit.

Green Lake, summer, 1991 - L to R: Chris Holmes, Jason Ries, Kristin McCarthy, me, Joe Blidy. Name of the boat: Aqua Fury.

Back to Amy’s café: Jason had been at the Goose Blind, too, and knew I had visiting Kristin in mind. Now he was proposing a more permanent visit to the Bay Area. It was a jaw dropping moment, mostly because I knew in the back of my mind that I was going to go through with it.

There was a part of me that really did want to stay in Madison. I recalled something Derrick McBride of Ivory Library said to me during one of our blues jam drinking powwows at the O’Cayz that resonated: “People who move to big cities are just followers.” But after I graduated and had been back to the sleepy suburb of Villa Park for a week, I wasn’t so sure how strongly I felt about anything. The seed was planted in my head now. If it didn’t work out, I could just move back. I decided right then and there to say yes. Yes to San Francisco, yes to moving completely away from my provincial little dichotomy between small Midwestern town and big Midwestern city with Madison in between, yes to maybe some better opportunities musically and yes to seeing Kristin again. And yes to one more pitcher.

The next morning, I broke the news to Greg Norman. He didn’t seem too bummed out about it. He was already practicing in a punk-funk band called Creature Custard, and in a band I can best describe as “harder than Creature Custard,” Natural Cause, that gave him more of an outlet for his ability to absolutely shred it on bass. I sat in on one of their practices. They were hardcore, and Greg seemed right at home. It was time.

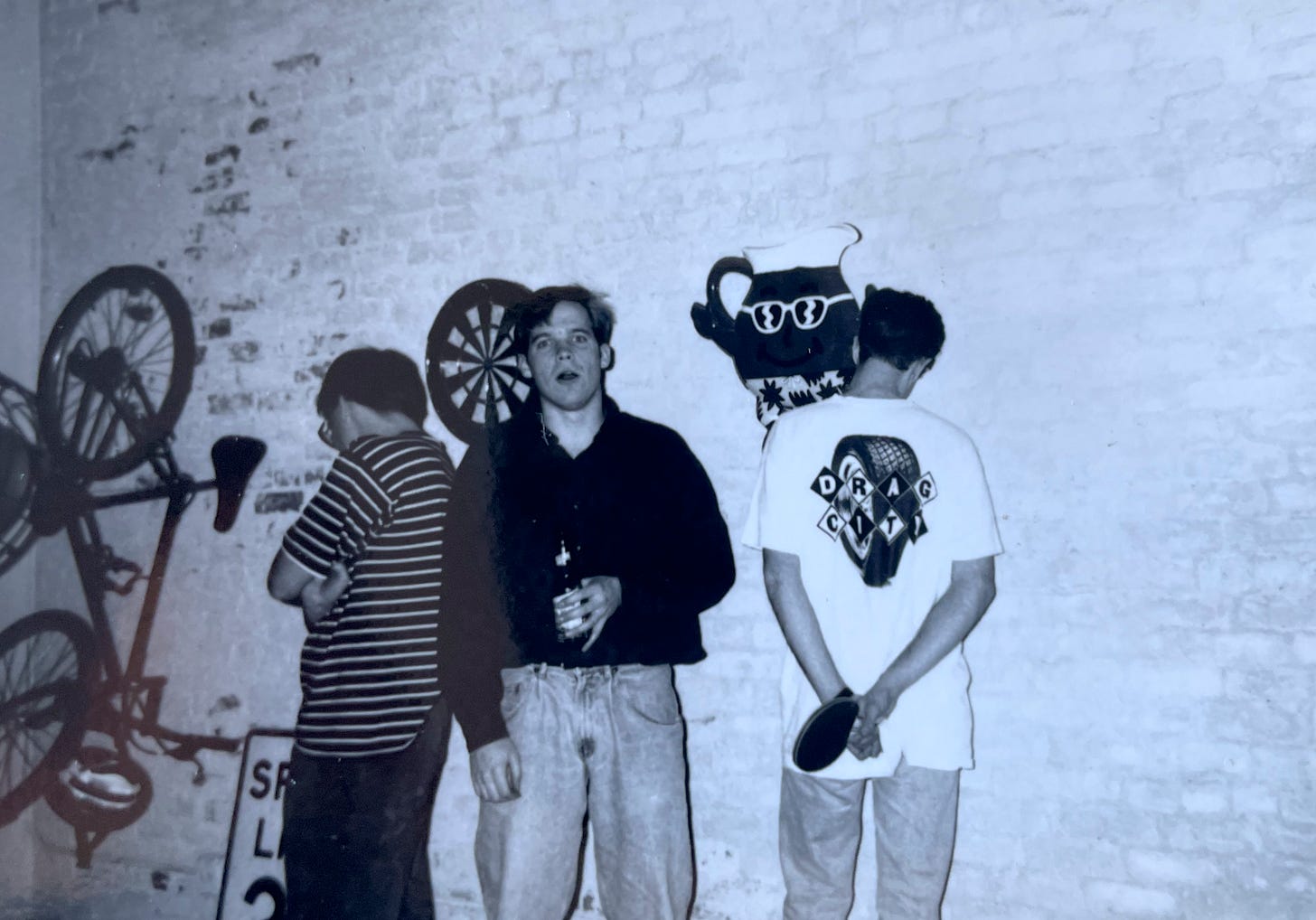

During that fall, I worked with my dad to save up money for my trip out west. John Dannenbrink and I continued to take weekend trips up to Jagielo’s studio to finish the Plymouths recordings. If there is one thing I’ve always done, it’s to finish what I’ve started. Even when it became clear that making an actual working band out of the Plymouths was going to be physically impossible, I felt strongly enough about what we were doing to hope that maybe we could shop it around and put something together. After all, if Pavement could do it with people living on opposite sides of the country, why not us? In a move that was somewhat desperate, I staged a fake band photo with my friends down in Chicago, purportedly to shop tapes or get gigs...or something.

L to R: Joe Blidy, me, Chris Holmes - Fake Plymouths promo. Too slick for Drag City.

Just before Christmas, we put the finishing touches on the mixes and I came home with a fresh cassette of “Cruz Is the Lilac,” the only proof I had, for years, of what we had accomplished.

John, with TV closeup pic of Cruz1 from Santa Barbara

In the new year, I’d be off to San Francisco. There would be no shopping around les plymouths. John would soon renounce the creation of music as a form of idol worship, become a member of the Russian Orthodox Church and disappear to Wasilla, Alaska.

Look for lights when you hit the coast

On January 3rd, 1993, Jason and I packed my ’77 Plymouth Fury dangerously full and headed west. We stopped for lunch at a sports bar in Springfield, Illinois and watched the Houston Oilers blow a thirty-five-point lead over the Buffalo Bills in the second half of the AFC championship game. Whenever they show highlights of the game during the playoffs each year, I remember thinking, that day in Springfield, “oh shit, we’re actually going through with this!”

“That car’s a digger!” L to R: Jason Ries, me. 1977 Plymouth Fury, fully loaded, dead of winter, 1993.

From Springfield, Jason and I headed south, eventually reaching Austin, Texas. Traveling straight west on I-80 is the quickest route to SF but there was bad weather there at the time, so we decided to head to warmer climes and take the I-40 route west, revisiting places across the south we’d been to the previous spring break, like Austin. On the night we stayed there, I decided to thumb through the papers and find an open mic. I found one at the Austin Outhouse. We went in while a blues guy was wailing on guitar, and I walked right back out the door. I put my guitar in the trunk and slouched and sulked in the driver’s seat as I drove us off towards the nearest Motel 6, thinking to myself: Way too much talent in Austin. They wouldn’t like the amateur shit I was doing.

Jason said, “What are you doing?” After all, we were moving to a place we had never lived with barely any ties. What’s the problem with playing an open mic? “You’re doing something different than the blues.” He was right. Fuck it! I screeched the tires in a U-turn, went back to the bar, signed up for the open mike and played three new songs.

There weren’t that many people in the club. It was an off night, but the people who were there seemed interested. A folk singer who played earlier introduced herself after my set. She had the same last name as me, Marie Swan. Marie had just moved back to Austin from San Francisco. She was homesick and discouraged because her car had been broken into one too many times and she’d also been mugged in the Tenderloin, the notorious downtown neighborhood known as the epicenter of chronic homelessness and drug trafficking. This triggered my memory of a song by another folk singer, Michelle Shocked, from her “Texas Campfire Tapes” album, called “Fogtown,” which painted a picture of the city we were heading to similar to Marie’s:

When a city's got the charms of a painted lady

When survival bites like a black-haired bitch

You can find yourself on the closest corner

You want to stay, you want to go, you got the Fogtown itch

I was beginning to get a darker picture of my destination and Jason and I had half a mind to stay put in Austin. But Marie Swan was helpful, giving me a few club addresses out there. One was a bar called The Albion.

After Austin we spent a couple of days in Big Bend National Park and the Fury was beginning to show signs of stress. We stopped at a gas station somewhere in West Texas, and a guy who talked like Roscoe P. Coltrane from the Dukes of Hazzard said, “That car’s a digger…you gonna get yourself some post holes!” We both looked at each other and said “What?”

Later, at a gas station in Flagstaff, Arizona after staying the night, with Vegas as our next stop, the guy held us up from leaving after filling ‘er up and told us he’d like to have a look at those springs in the back. He said the springs were bent and about to break, and as it was, the car was already resting on the rear axle. So that’s why Jason’s calculations of our gas mileage weren’t adding up. Had we gone much further the rear axle might have broken and there we’d have been in the middle of the desert. After getting helper springs, we decided we’d gambled enough already so we skipped Vegas and hauled ass to our final destination.

We arrived in San Francisco on the evening of the 11th, and it was raining pretty hard. It rained there for the next two weeks straight, in fact. There was no dramatic, inspirational entry into the city, the likes of which I’d been told about in a letter from Kristin, about a year before, describing the crossing of the bridge into the bright lights of what Herb Caen, the famous San Francisco newspaper columnist coined “Baghdad by the Bay.” My first impression was nothing like what I’d read in Frank Norris’s McTeague the previous fall or anything coming from Herb Caen’s typewriter.

Since we took a southern route into California, we came to the city from the south up Highway 101 along the peninsula, passing an inscription on a hill in bold, block white letters that read “South San Francisco, the Industrial City,” where we stayed the night. The strange, “Legoland” rows of houses that crisscross the hills of the Bayview and Excelsior districts were the only thing we’d never seen before. We were just happy to make it in one piece after the car trouble. Had we crossed the Bay Bridge from the East Bay we might have had a more dramatic moment, but because of all the rain and fog, I doubt it. There would be no bright lights when we hit the coast, just fogtown.

Like driving in fog, my focus was on the events immediately ahead and my nose was straight down. I was staring at the proverbial white line on the right-hand side of the road, trying not to lose it. I needed to find a job, and fast. We considered moving on, up to Portland to try our luck there. There was no spectacle to be found in our underwhelming entry to the most beautiful city in the U.S.A. We crossed the line to the City and County of San Francisco “not with a bang, but a whimper,” as T.S. Eliot says.

I found a temp job in a mailroom and then got right down to work on the musical front. Within a couple of days I took Marie Swan’s advice and signed up for an open mike at The Albion, at 16th and Albion in the Mission. There was a power outage earlier in the evening that kept a lot of people away that the rain already hadn’t, so I was able to play a mini set of about six or seven songs to a small group of unsuspecting drunks. The Albion used to have a back room that was closed off to the main bar and they had a little stage there. Out front, above the main bar, was a sign that said, “service for the sick.” I remember that sign made me think this would be a tough crowd as I was walking in, but things turned out all right.

Because of that open mike, I landed my first solo gig on February 18th there, barely over a month later. I opened for a singer and piano player named Alison Levy, who would later book shows using her full name of Alison Faith Levy. I’d get to know her because she and I would one day have mutual band mates, and she knew some folks from Camper Van Beethoven, one of my favorite SF bands. She was in the audience at the Kilowatt – just across from the Albion as it would turn out -- after Beulah’s very first show as an opener for the Olivia Tremor Control four years later. She asked me how the hell we landed that gig.

The booker at the Albion was an older woman named Jano who lived in Santa Rosa. It seemed like she was hitting on me when she hopped into my Fury to “help me park it on a good street in the Mission,” the night of the gig. I pretended to be naïve. She made fun of it later. I think.

I was moving as fast as I could to get something going musically, but San Francisco was a lot bigger and more intimidating than any place I’d played before. Where Madison had a small number of clubs, SF was spread out all over the place, separated by hills, and you didn’t get the sense that there was a very tight-knit musical community. In later years I’d learn that many people I’d seen early on were connected to people I’d meet and play with, so things were closer together than I thought. But these things take time. I had never even broken all that far into the scene back home, which may explain why I left. Nevertheless, the comfort I had in Madison, of being in a community that struck a balance between the only two places I’d known before, was thrown out the window and completely out of sight. The west coast was foreign to my Midwestern sensibilities, but I plugged away as best I could.

I put out ads in BAM magazine, a local rocker mag that no longer exists, and also called a few people from the ads already in there, with little success. A little later I got a call from Adam Cohen, answering a handwritten ad I put up in a coffee shop on 16th at Valencia. He was in a band that would gain some recognition, The Mommyheads. They were looking for a bass player or “whatever.” I would fall into the “whatever” department. But it really was a bass player that they needed. They had everything else covered.

Adam came over to my apartment and played me a tape of a single they were releasing called “Day Job,” and I was hooked. He said he was into XTC, especially their record Drums and Wires. Greg Norman would have been a perfect fit on bass. I was no bass player, it’s one instrument I never really tried to play. They would bring in Jeff Palmer, whose playing reminded me of Greg’s and that lineup would last for a good long while. I became a regular at their shows. I loved them, especially their record from before they moved out west, called “Coming into Beauty.” Their recorded output once they arrived in SF in 1991 was a smattering of EPs here and there, all pretty much self-released. But their live sets were fantastic, and it wasn’t long before they got noticed.

The Mommyheads would get labeled “the next big thing” in the local papers, sign to Geffen, put out a record produced by Don Was, get dropped by Geffen, then go on a ten-year hiatus before reforming back in New York, where they grew up.

“The next big thing” would not be something I’d achieve as a bandleader. What follows is three years of trying to figure out what kind of artist I wanted to be, and what kind of band I wanted to be in, while Beulah came about when I was least expecting it.

[Next chapter here.]

In one of Jeff’s desk drawers, there was a random closeup pic of a TV screen, and John recognized the face of the man in the picture as Cruz, from the Soap Opera “Santa Barbara” which ran from the 80s to the early 90s. John had a song lyric that went “She is the lilac,” so, punch drunk at this point, we made this picture our album (tape) cover and called it “Cruz is the Lilac.” Just in case you were like, “WTF is that?”