College band(s). Some Madison, WI history. Part II out of III in a series of learning how to lead a band by trial and failure…

Troubadour

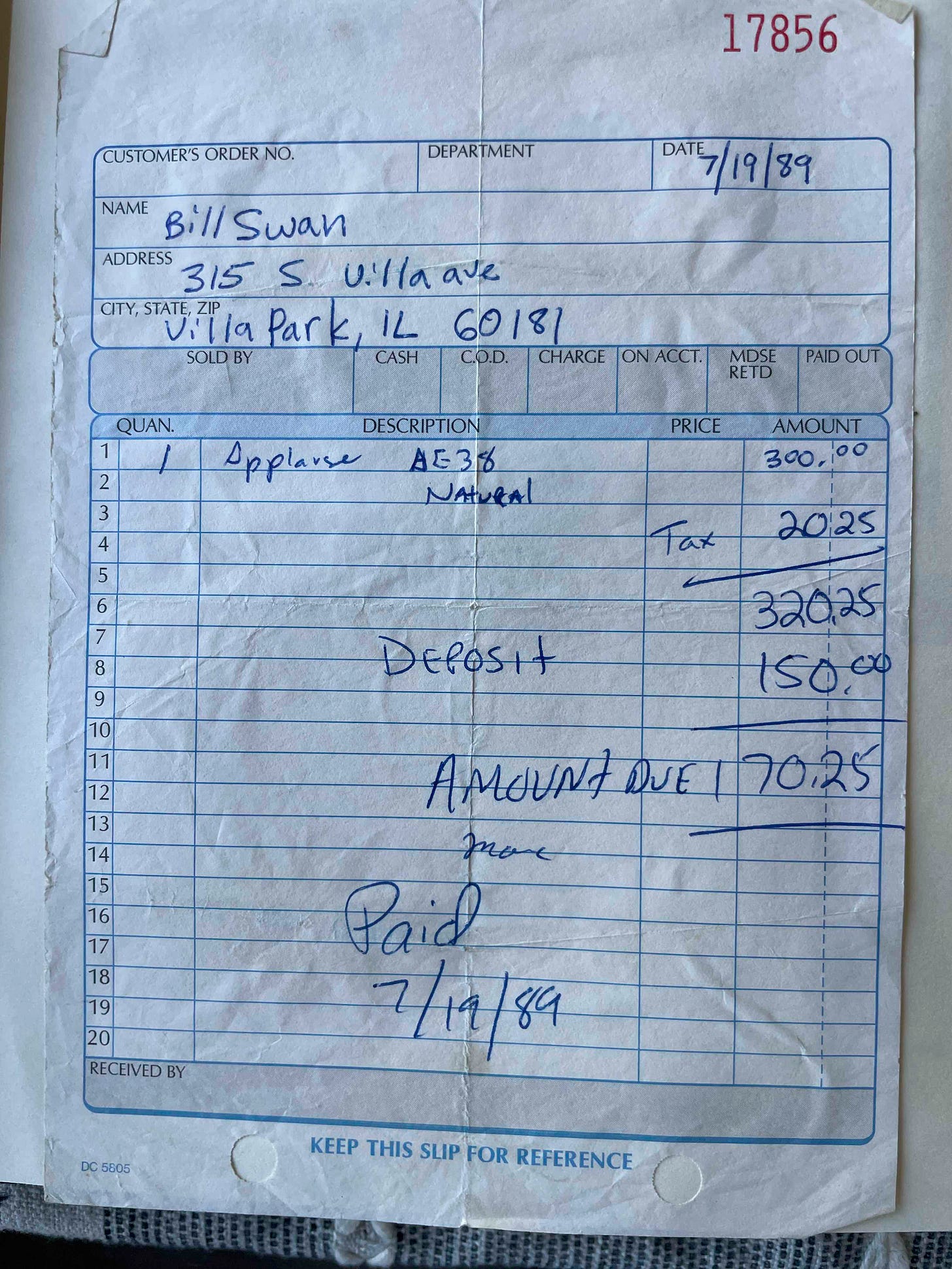

I bought my first acoustic guitar in the summer of ’89. I couldn’t get an Ovation, so I had to settle for the Applause.

Up until then I was recording stuff on a borrowed four-track but I had to give it back. I became dependent on someone else’s multi-tracking device to be able to sing along with my guitar playing or whatever I was trying to map out musically, just as I was dependent on whatever my high school band was coming up with in order for me to sing along.

I decided I needed to learn how to sing and play guitar at the same time, live, stripped away from all artifice -- just me, in a room. I would learn how to perform from the ground up. I chose an acoustic-electric guitar so I could play in a room and also be able to plug it in if I happened, by some miracle, to get a gig somewhere that had a proper stage and PA. After that, a whole bunch of songs came pouring out.

This was the start of what would become a meticulous, prolific routine for the next seven years: When I had the seed of a song planted in my head, I would work it out on that guitar, humming a vocal melody, then putting words to it until it was completed, no matter how good or bad it would end up being. Then I would tape it live onto a normal tape recorder after finishing it and write the finished lyrics into a notebook. I could do one of two things from there: Send out songs somewhere to get solo gigs or present them to whatever band I would end up being in and have the members of that band pick their favorite ones. At that point we’d hash ‘em out together.

This was my lab school of songwriting -- a lot of quantity, with little to no quality control. On the other hand, I would soon learn that sometimes others would like the songs I wrote that I thought were throwaways, and vice-versa. I kept busy at it all summer long. My mom started calling me her little troubadour. So, I wrote a song about that:

Well, I can sit and play guitar and sing for hours

and watch the day go by

Watch the people in their cars, children on their bikes

Hustle and bustle ‘til they die

And I think of my fears of losing my life

to the system, rules, clichés and flack

But I can’t

Believe I’m gonna fall into that trap

I’m gonna be a troubadour

Well, I sit in my abyss, think of this

and the money it could bring

But I really don’t want to bow down and kiss

some President’s diamond ring

So I’ll wait until I die

and let someone discover my “gold”

and while my children will fight for what’s theirs

I’ll be turning into mold

‘til then I’m gonna be a troubadour

Lyric writing was still a work in progress. As for the abyss, that was the basement in Villa Park, where I was living that summer since Tom had moved back from California. But not for long...

Back in Madison, armed with my new guitar and a bunch of songs, I started meeting people in the dorms my sophomore year that I felt comfortable performing in front of. One of those friends, Brad Thayer, I met on the first night we moved in and took a liking to instantly. He was the first New Yorker I ever befriended. Brad’s roommate, Geoff Herbach, had a dad from Brooklyn, so they bonded over that, but Geoff himself was from a smallish town like me, Platteville, WI -- so we bonded over that.

This group of friends came at a pivotal time in my life. Geoff heard “Troubadour” and had me thinking that I was destined to become a star. Soon thereafter I worked up the courage to play an open mic at the Memorial Union. It was hosted once a week by a local singer/songwriter named Marcus Bovre. It so happened I had just heard him promoting a show for his band, Marcus Bovre and the Evil Twins, along with a live solo set and an interview on WORT, the local college radio station, so I already knew who he was. “Great set,” he told me. Had I not gotten some early feedback like that, it wasn’t likely I’d be an aspiring artist for much longer. I give credit to Geoff Herbach especially, for his positivity and the encouragement I needed to keep going.

Brad also played guitar and had an amp in his dorm room. He could play Zeppelin solos while I was still trying to get a handle on an open “b” chord. The wheels were spinning in my head. Brad and I got drunk on Mickey’s Bigmouths one night and decided we wanted to start a band, so we drew up all of these funny “Drummer and Bass Player Wanted” flyers. This is the only one I can remember: “Need Bassist and Drummer. Don’t fuck around, call: Bill or Brad.” Brad also came up with our name that night: The Holsteins.

L to R: Geoff Herbach, me, Brad Thayer. Their dorm room, not mine.

We never did put out the ads. Then, sometime near the holidays, another dorm pal of mine, Jim Dixon, introduced me to a bass player friend of his from high school named Greg Norman, not to be confused with the Australian golfer (or Greg Norton, from Hüsker Dü, for that matter).

Once we got talking, I could tell he was legit. And once we started playing -- let’s put it this way: Greg Norman was the best bass player I have ever worked with. And I’d be fortunate to work with some great ones. He could thrash with fuzz distortion, he could play funk, jazz and wrote catchy, melodic lines like Paul McCartney. He could play upright. He also brought some guitar-based songs, and he could sing harmonies. Greg had been working with an acquaintance of his who was a couple of years older than us, who also went to his High School, Dave Konkol, on drums. Greg and Dave joined us as a package. The Holsteins doubled in size.

A few weeks later we began practicing in the basement of Sellery Hall, the dorm adjacent to mine where Greg was living. I plugged in my acoustic-electric through the PA they had, and we worked up a set.

L to R: Dave Konkol, Greg Norman, notebook of songs with “sucks” written in whiteout under Chicago Bears helmet sticker; Basement, Sellery Hall, UW-Madison

We did this routine for a short while but then Brad quit, saying “I didn’t think it was going to be that serious.” The real reason was that he couldn’t stand Dave. “Dave is an offensive human being,” Brad would say later.

We did record a tape of songs that winter in early 1990 with Brad agreeing to play lead guitar on it after he quit. This captured a period I could best describe as folk rock, since I played acoustic guitar for the most part. Mike Zirkel recorded us. He also went to the same high school in Wauwatosa, a suburb of Milwaukee, as Greg and Dave did. Mike was about to move to Florida to go to recording school, so he was looking to get in a little more practice rolling tape. He would graduate with distinction and later became Senior Engineer at Butch Vig’s Smart Studios in Madison.

For those readers who might not know, Butch produced Nirvana’s “Nevermind,” among many other things. I’ve never met him1, but he’s from a small town in Wisconsin like mine: Viroqua, population about the same as Berlin.

Mike Zirkel, who was still working at an audio store in Milwaukee in 1990, brought over a bunch of rented gear and recorded our demo in Greg’s dad’s basement there, live to two-track, with a snake running up the stairs, out the house, across the driveway and into the sound board and tape machine in the garage. Mike froze his ass off out there, enduring take after take of botched solos or forgotten words peppered with “fuck!” Recording a rock band live to two-track under pretenses of making an album is a pain in the ass as it is – one mistake by someone and you have to start all over again. Wisconsin winters are no joke, so that didn’t help.

We called the recording “Live from the Catbox.” Even though it could have been called “Icebox,” “Catbox” won out because the basement smelled like a litter box.

The Holsteins didn’t last long as our band name. By the time we recorded that first demo and not long after Brad left, we changed it to Spin Cycle. The basement practice space in Sellery Hall happened to be next to a laundry room.

Spin Cycle was also the name of a song by two bands I liked: Irish band That Petrol Emotion, and Molehill, a San Francisco band passing through that summer who set up a guerilla show with a small kit and tiny amps outside one afternoon near Library Mall (UW Madison’s “Quad” area). One of Molehill’s members was Kyle Statham, who I’d run into again many years later when Beulah played a show in Seattle opening for his more well-known band, “Fuck.” Molehill was an unexpected surprise as I was walking through Library Mall, and I bought this tape:

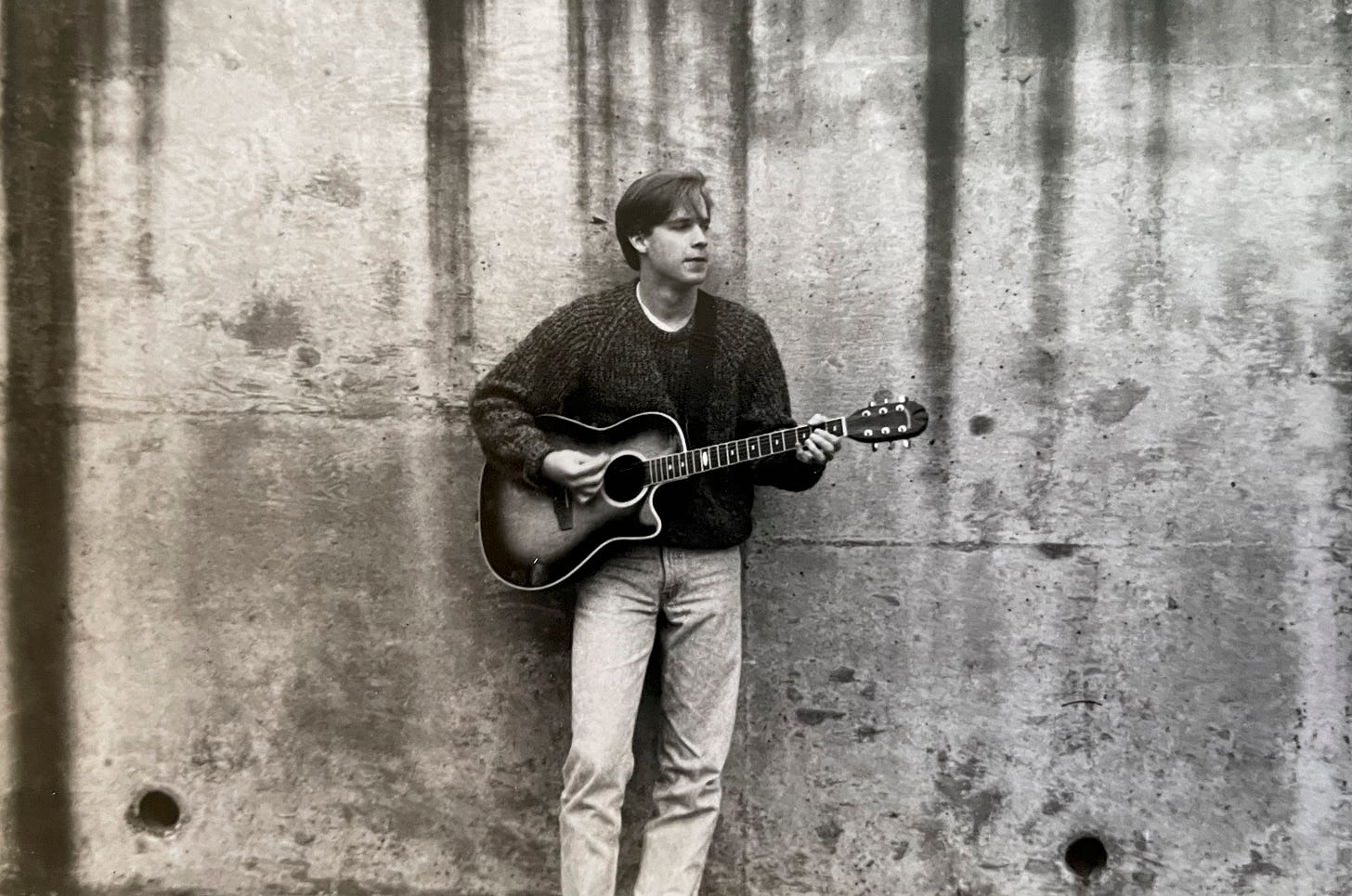

The summer of ’90 came and went. I managed to land a solo gig at the Memorial Union terrace in July. Credit for this promo photo goes to Matt Rogers, a friend of Brad Thayer’s who would later become roommates with Brad, Geoff, Jason Jones2 and me the following school year:

Spin Cycle would practice in the basement of the house my friends and I moved into during that next school year, and it didn’t take long for the band to wear out its welcome, as we had gotten a lot louder after the whole house agreed we could practice down there.

It was around that time that I bought my first proper electric guitar and amplifier with some pedals. The guitar was a 1974 Gibson ES-325 semi-hollow body and the amp I chose was a Roland Jazz Chorus. That would turn out to be an odd decision, as I hate the sound of chorus on guitar, but the clean tone sounded good, and it had 120 watts of power. I felt the need for distortion later, so I also bought an “Overlord” pedal. My grandma Kay had passed away that September, and I ended up with a little money which went to all that instead of my college education.

Since we no longer had a lead guitarist, to make up for my lack of riff playing and solo shredding, I tried to overcompensate by turning up the distortion on the Overlord to make a racket or by strumming really fast. I used to say that I aspired to be the best rhythm guitarist in the world. I was too lazy to learn solos. Somehow I equated fast strumming with good rhythm. I’d learn subtlety, when and when not to play ahead or behind the beat, and to slow the fuck down much later. Greg’s bass playing and Dave’s drumming became busier to compensate for the lack of lead guitar licks. By this time, we were listening to trios like fIREHOSE and The Minutemen, and that influence became clear (except I couldn’t play solos like D. Boon). My singing in this period sounded awfully similar to “Look Sharp” era Joe Jackson when I listen to it now. In a word, we were hyperactive.

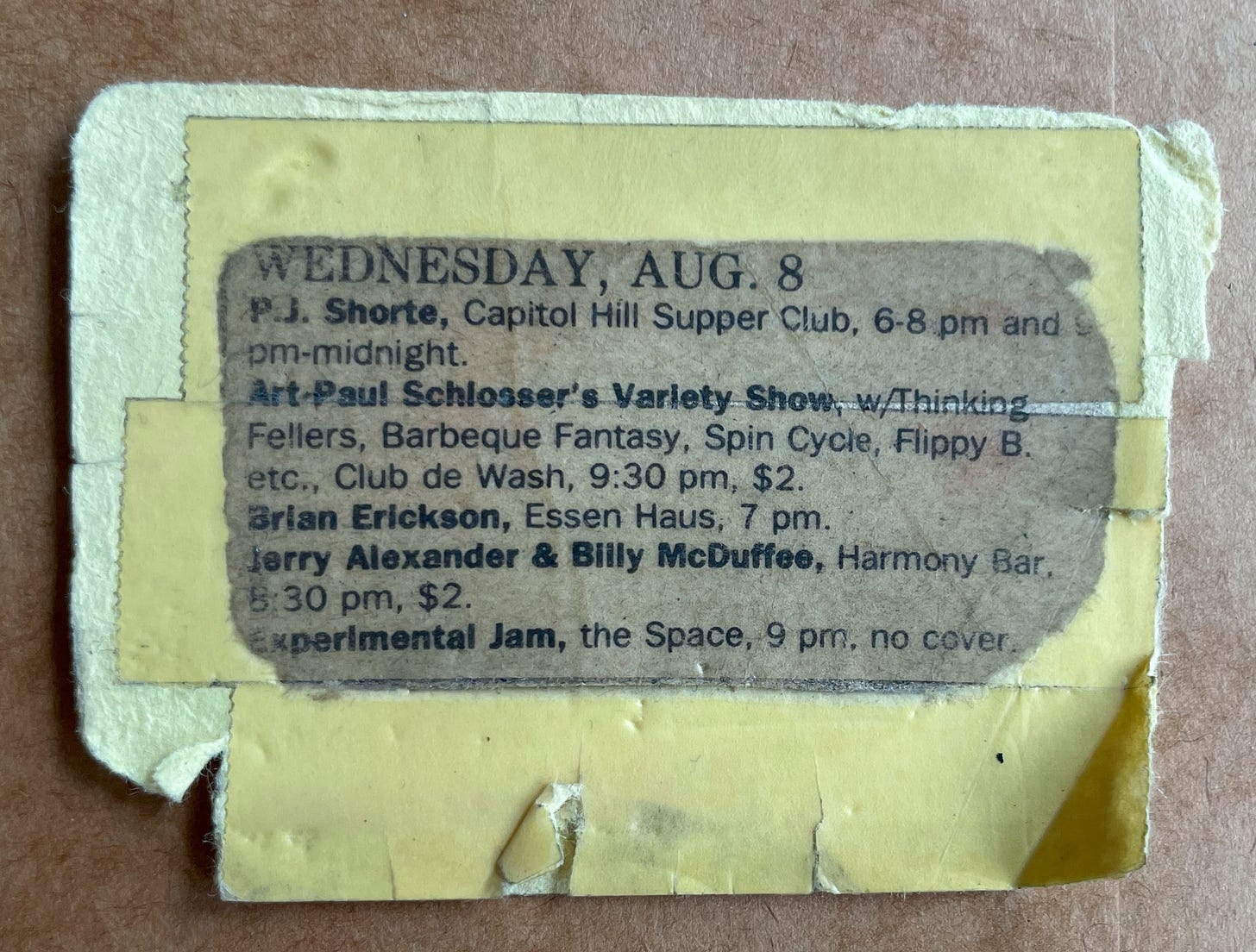

It took a while, but we finally landed a club gig at Club de Wash, a smallish but not tiny room in the old Hotel Washington complex of bars, including a speakeasy called The Barber’s Closet, and Rods, a “biker” bar in the basement.

I’m afraid I could only find this photo taken at the complex:

Club de Wash was one of two clubs that size that attracted newer, up and coming national acts looking for a stopover between Chicago, Milwaukee or Minneapolis, so getting a gig there as a local band was a bigger deal.

I had joined the Memorial Union Music and Entertainment Committee – mostly as a way to get to know people to try and book my own band, which pissed most of them off. I mean, it was a stupid, unethical thing for me to try to do. We’d get blacklisted later. There was a sheet next to the phone called “wannagig bands,” and we were at the top of the list. They were in charge of booking shows at the student union: An indoor space called Rathskellar and, during the summer months, the outdoor terrace on the waterfront of Lake Mendota.

Before we were blacklisted, I met a self-proclaimed “Jewish rapper” named “Flippy B” on the committee. Flippy, I think, was the one who got me the solo gig at the terrace – they were likely desperate to fill afternoon slots during the quiet summer months -- and later had his own gig at Club de Wash, managing to get us on the bill. The gig turned out to be a “variety show” hosted by a local street musician named Art Paul Schlosser who sang songs like “My Cat Was Taking a Bath.” He was terrible.

The headliner for this show was the San Francisco band Thinking Fellers, before they added the “Union Local 282” part. I remember thinking that they were pretty high on some kind of psychedelics. I figured it was a California thing, not that I had any basis to judge. At any rate, it was certainly a memorable experience, and it was not good. Art Paul stopped our set. I suppose that was a humbling moment, getting the hook from a monotone singer of songs meant for small children halfway through our inaugural gig.

I carried this newspaper clipping in my wallet for twenty years. It served as a reminder that persistence pays off.

It might as well have said “Puppet Show and Spinal Tap.”

I’d see a lot of good shows at Club de Wash over the years, but our gigs there would never be good. I think the place was cursed. It would later burn to the ground.

I saw Pavement there in 1991. When I paid my money at the door, I bumped into a severely drunk dude that looked like a hippie who just climbed out of a dumpster. He was wandering aimlessly, spilling his beer and tripping around through the crowd. I said to myself that he must be new in town, because in a place like Madison, you knew all the street people by name. And then he walked onstage, sat behind the drum kit and never missed a beat! Guys that drunk usually fall off of their drum stool, as I would witness when Mike Joyce of the Smiths did it, sitting in with the Buzzcocks for their first reunion tour, and I would soon find out firsthand in my own band. But not Gary Young, Pavement’s original drummer and engineer for their first record, “Slanted and Enchanted.” His liver was from a sturdier stock.

Strange Bedfellows

Spin Cycle lasted about a year or so, and then Greg came up with a more suitable band name, Strange Bedfellows. And strange bedfellows we were.

Dave was a conservative, loved Rush Limbaugh – you know the type. He idolized John Bonham as a drummer, but he often sported a buzz cut whenever he’d get back from a weekend of guard duty for the ROTC. He smoked a lot -- always seemed to have a ciggie hanging from his mouth when he played, an imitation of Bun E. Carlos from Cheap Trick. He was a good player though, very fluid, and indeed he knew his John Bonham. Interestingly, he also took a liking to the Stone Roses’ first record, and whenever I listen to the drumming on that record now, it reminds me of Dave. I liked his playing; his personality, not so much.

Greg was dead-on with the name Strange Bedfellows. Dave and I just didn’t see eye to eye. Brad was right: Dave was very offensive. I can’t print a lot of the things he used to say.

Though we all felt Strange Bedfellows to be a very appropriate and clever name, I don’t suppose it was that surprising how many people took it the wrong way. One night, at a party, I was chatting with a friend of a friend who happened to be in a frat. His name has been long forgotten (probably that night), but I will never forget the exchange:

“You’re in a band? Cool! What’s the name?”

“Strange Bedfellows.”

“Ex-CUSE me?!”

“Ever heard of the phrase ‘Politics makes strange bedfellows?’”

[Crickets]

Right around that time, Strange Bedfellows had put in a bid for the opening slot in a local festival gig being played at a place called the City Club. We got beat out by a band named Clip the Daisies, which we scoffed at. “Who the fuck are these guys,” we asked.

They had just moved up to Madison from Champaign, Illinois, and were one of the few local bands we hadn’t heard of and sized up. Greg and I went to the show. We were blown away. I remember thinking it was the end of the world, that I should quit being in a band right then and there. The alcohol was talking: They were the tightest band I had ever seen or heard in my entire life!

The drunker I got, the more depressed I became. I began comparing all the bands I liked with Clip the Daisies based on how tight they were. Talking Heads? Clip the Daisies were tighter. fIREHOSE? Poster Children? Nope. Led Zeppelin? The Beatles? Without question, not as tight as Clip the Daisies. How the hell were Strange Bedfellows going to compete with Clip the Daisies? Well for one thing, after the alcohol wore off, I consoled myself: Their lyrics were jokey. They had a song called “Sasquatch.” It was pretty much about bigfoot. I thought that was kind of dumb.

We opened for them at Club de Wash a little later and it was one of the worst shows we played. It was cold, and I broke three guitar strings in one song. “Wires tend to disconnect” was the only banter I could come up with. Like I said, Club de Wash was cursed. We were having a hard time attracting audiences, and that gig did us no favors.

We recorded another tape’s worth of material live to two-track with Mike Zirkel in the catbox around this time as Strange Bedfellows, representing who we were as a trio. I don’t think that tape did us many favors either. Mike recently put it up on Bandcamp. See if you can find it. Fair warning: my vocal affect is a tough listen. And if you like phase, you’ll love this tape!

By the spring of ‘91 we started playing out at Inn Cahoots, a tiny place just off the block surrounding the state Capitol. They later changed the name to The Chamber and the guys that booked shows for it were in our corner. We became regulars there; it became our home base. The Chamber was a fitting name; a room that would make a crowd of fifty people seem like a fire hazard.

That summer, Greg’s sister gave our tape to a friend of hers, Peter Bruhn, the drummer for Ivory Library, a locally acclaimed band that had been around a while. Derrick McBride, their bass player, and Jeff Jagielo, their lead singer, guitarist and songwriter, liked us and took us under their wing. They gave us a practice space that fall and some opening slots for them at the other club that supported up and coming national acts that would also one day burn down: O’Cayz Corral. Some of their fans seemed to dig us.

Ivory Library weren’t a huge draw compared some of the sludge, punk, funk, or punk-funk bands who were their contemporaries at the time like Tar Babies, Killdozer or Poopshovel, but they put out quality records with great songwriting and taught us about subtlety and spacing. “The ‘brary,” as Derrick called them, would have fit right in on 4AD records. They were sort of ethereal, incorporating influences such as American Music Club and Nick Drake, perhaps. Derrick introduced me to both.

Derrick worked for “b-side records,” the hippest little record store in town, and I’d often ask him what he was into. I was always broke, so I needed to know what records were good! Derrick also bartended the Tuesday “blues jam” nights at the O’Cayz Corral. He’d let me in for free and gave me drinks, so I went over there every week for a while to shoot the shit, either not paying attention to, or making fun of, guys who just didn’t have it. Once in a while, someone like Clyde Stubblefield, James Brown’s oft-sampled drummer from the 60s who lived in Madison by then, would show up with some of his cats to take everyone else to school.

Since I can’t find any good pictures I took of Ivory Library from that era, here’s one with an Ivory Library poster on my bedroom door, R (Never mind my friends Dan & Chris Holmes whetting their appetites).

Before Strange Bedfellows moved into the practice space with Ivory Library, we had a shakeup. Dave Konkol started playing for a cover band at frat parties as it would make him a lot more money. This experience had an influence on his thinking towards our band as well. He came to practice one night, drunk, or maybe on coke, with a list of demands: I would be the rhythm guitarist, and we would bring in another singer and a lead guitar player. We would play covers, Greg’s songs and few, if any, of my songs. Are you sensing a little déjà vu? Play more covers, make more money.

Greg and I said “nope,” so Dave quit. We put out an ad and found a new drummer, Todd Ison. We had one practice, and then Dave begged to come back after getting kicked out of the cover band for being so drunk at one of their gigs, that he fell off his drum stool in the middle of a song. Todd (who would end up doing the same thing for us about a year later) was bummed, but patiently stood by. We gave Dave a second chance, but it wouldn’t last long.

Before the summer was over, Dave and I got into a heated, drunken argument, God knows about what. The end result was me screaming to him that he was out of the band, and him screaming back that I couldn’t kick him out because he quit. Real original. Then we called up Todd and asked him if he still wanted to be in the band and he showed up for practice the next afternoon. Dave dropped out of college and moved back to Wauwatosa not long after that. I never heard from him again.

Strange Bedfellows taught me the praise and pitfalls of trying to lead a band, how to present your songs, and that history repeats in the band dynamic. It was probably a “how not to” more than anything, the beginning of a long stretch where I’d be the one presenting the songs and (mostly) having the final say. There were times when I wished I could be in a band where someone else was calling the shots, thinking maybe being the leader wasn’t my forte. But I’m glad I did it for a time because it made me a better supporting cast member when I took on that role later in Beulah.

When Todd joined Strange Bedfellows for good, our sound changed, and we had more of a musical consensus. We didn’t change our name, though. We would embrace the strange.

Greg Norman (captured during a brief shaven period), Todd Ison

Todd was a theatre major at the UW, and brought that theatrical approach to the drums, which made him interesting to watch. I was listening to a lot of XTC at the time and Todd told me they had always been one of his favorite bands. He wasn’t the most technically gifted drummer, but he accented things in unusual places – there were more things for both Greg and I to play off of rhythmically. Todd Ison was an interesting dude, definitely an intellectual; a welcome change from Dave, but I sensed he had a dark side.

Strange Bedfellows became more of an arty band and less of a “rock” band. My Overlord pedal got stolen (I think it was someone from the West Wash apartment who got fed up with us), and I decided not to replace it. As grunge was moving into the mainstream, being the knee-jerk contrarian that I am, I said I would only play clean tones as an act of defiance. I was arrogant enough to say that sloppy rhythm guitar players would hide behind their distortion.

Speaking of strange, my lyrics during this period were getting so obtuse that I look back at them now and I just have to say “huh?” I wonder what the hell I was writing about. Here’s a passage of a song I called “In the Hall of Frame” which is probably the worst example of this:

Pass a glance across a brazier table

Sense a grim kind of “hardly able”

They set the papers down, down on top of the coals

you gotta wonder how

these papers see it through to glass—

reflection mirror poses in the hall of frame

I was not doing drugs, but there was something going on upstairs. A reviewer for one of the local rags at the time wrote this in a review about one of our shows: “Bill Swan is the devil in his pants.”

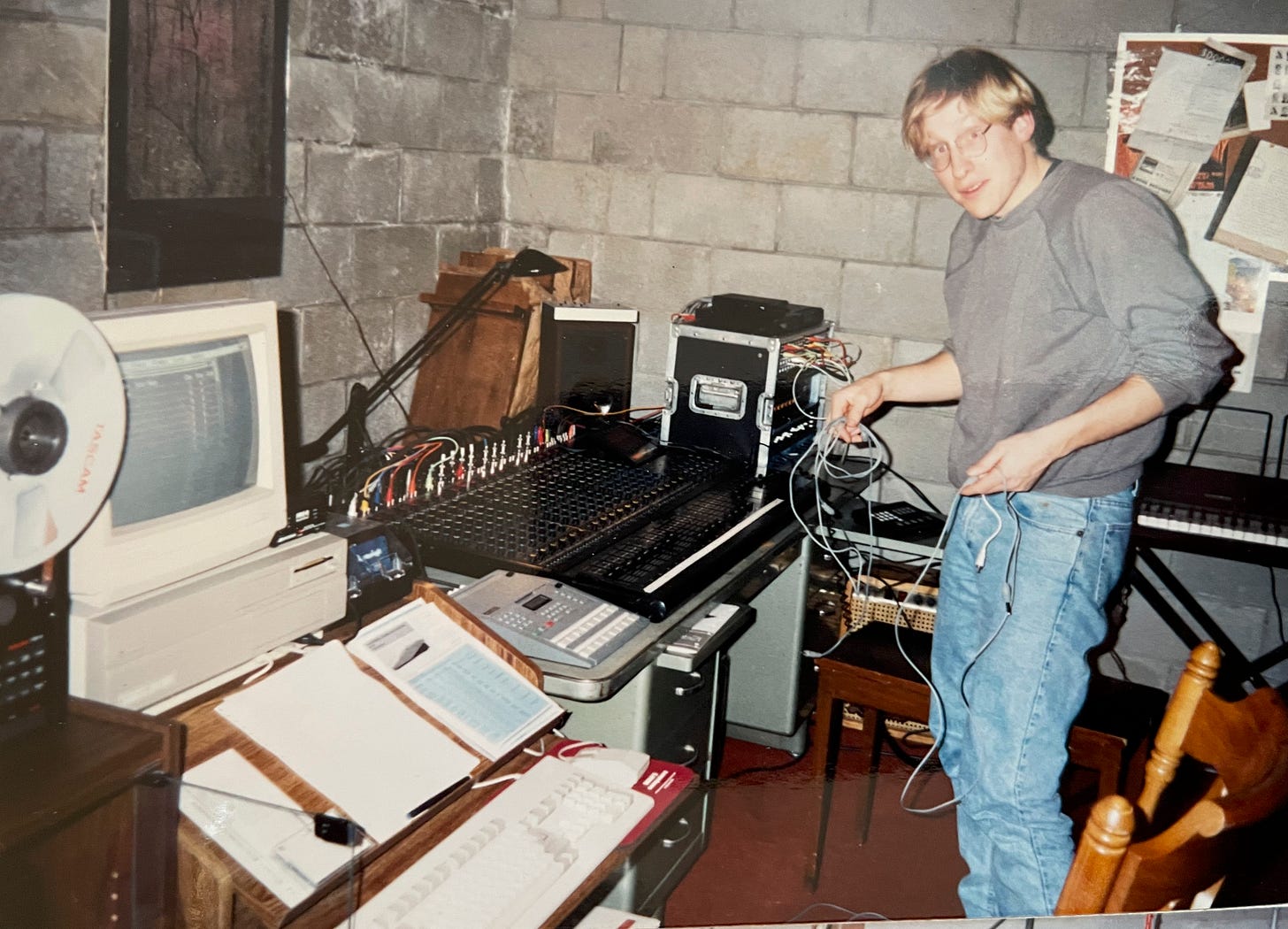

In the winter of ’91 - ‘92, Jeff Jagielo of Ivory Library offered to record us for free at his home studio about an hour north of Madison. He had a decent reel to reel tape machine, good mics and cool outboard effects. I hadn’t had much experience multi-tracking in a studio setting before that. Zirkel’s recordings were live to two-track. Absent Presence did do a multi-track recording of a couple of songs back in ’88 but we were paying this dude LeRoy on the clock and didn’t have the luxury to take our time. It was clear he wasn’t into the project, which made it that much harder to fork over money. Not only was Jeff Jagielo truly vested in the project, but he also used it as an opportunity to learn. I consider him to be an early mentor. We could take our time.

Jeff Jagielo, exercising proper cable management, Plover, WI, (Winter ‘91-92)

This recording became Strange Bedfellows’ only record, which we called “Down, Down, Down.” I say “record,” but we only really printed up cassettes. And by the time we got them pressed, with colorful pictures of the three of us drowning in a sea of pillow feathers (Todd’s idea), we were approaching the summer of my senior year in college. Before I knew it, I would end up in San Francisco.

[Next chapter here.]

I was never formally introduced anyway. We did cross paths once. Spin Cycle (I think we were still called at the time) opened for Fire Town, which was one of Butch’s short lived bands in the late 80s, early 90s, at the Rathskellar at the Memorial Union in Madison. Or it might have been the re-formed Spooner, not Fire Town. I don’t remember for sure. Spooner was his older band that had gotten back together after Fire Town disbanded.

Earlier versions of this chapter included a paragraph about parties and drunken dorm room songs we’d all write, such as “I Lost My Virginity to a Drunken Jason Jones.” It didn’t make the cut. I feel bad, as this ended up cutting Jason out of this story entirely, though he’d probably be grateful for that.

Reading this was a wonderful memory. Damn I look so young and see faces I’ve not thought of for years. I thank Bill for his awesome compliments. We were learning a lot of things that would help in dealing with/ developing groups in our futures.

"Bill Swan is the devil in his pants." is a... very interesting quote. Might want to throw it in your obituary when the time comes.